The Pillar Two GloBE rules apply a jurisdictional blending approach when determining the GloBE effective tax rate (ETR) for a jurisdiction. This blends income and taxes within the specific jurisdiction, effectively meaning that income taxed at a low rate is blended with other income that may be taxed at higher rates.

The GloBE rules do not allow global blending and they restrict blending of income and taxes with other jurisdictions.

One of the exceptions to this relates to CFC taxes.

CFC taxes incurred by a parent entity are pushed down to the CFC entity for the purposes of the GloBE rules.

This means that CFC tax incurred in one jurisdiction is accounted for in a different jurisdiction when calculating the jurisdictional GloBE ETR. This could, for instance, result in a jurisdiction that would otherwise be a low-taxed jurisdiction, being allocated taxes from another jurisdiction such that its GloBE ETR was then increased to at least 15% with no top-up tax due.

The OECD recognised that the CFC pushdown could be used to manipulate jurisdictional ETRs and included a limitation on the amount of tax that could be pushed down.

However, the definition of CFC taxes that are restricted in the GloBE rules is much narrower than under many domestic CFC regimes. In this article, we look at this issue.

CFC Pushdown Limitation

Covered tax that relates to passive income allocated to CFCs is restricted to the lower of:

This is provided by Article 4.3.3 of the OECD Model Rules.

Any remaining covered tax is allocated to the owners (eg the company with the CFC regime in place).

This ensures that the tax allocated to a CFC in relation to passive income is sufficient to reach the 15% global minimum rate and does not artificially increase the covered tax of the CFC entity (which would increase its ETR and reduce any potential top-up tax liability).

Passive income is defined as:

– dividends or similar payments;

– interest or similar payments;

– rent;

– royalty;

– annuity; or

– net gains from property that produces income listed above.

Pushdown Limitation – Example

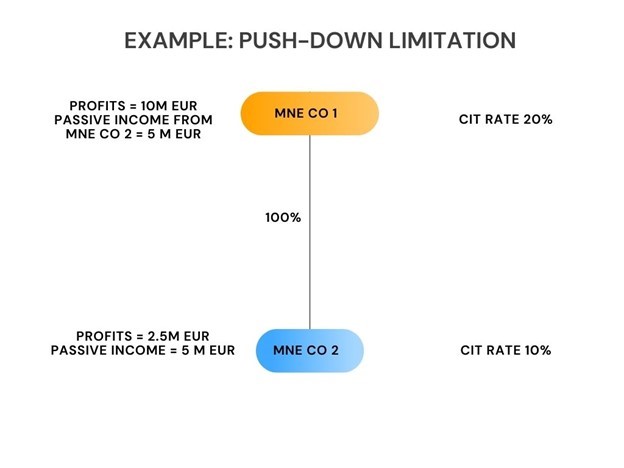

MNECo1 is part of an MNE group subject to the Pillar Two GloBE rules. It is resident in a Country A that has a domestic corporate income tax rate of 20%.

MNECo2 is a wholly-owned subsidiary of MNECo1 and is resident in Country B, which has a corporate income tax rate of 10%.

Country A has a CFC regime which taxes the foreign passive income of MNECo2.

MNECo1 has profits of 10,000,000 euros and is additionally taxed on foreign passive income of MNECo2 of 5,000,000 euros.

MNECo2 has trading profits of 2,500,000 euros and taxable passive income of 5,000,000 euros.

The tax in MNECo1 is 15,000,000 * 20% = 3,000,000 euros. In addition, it can claim a foreign tax credit on the CFC income of 500,000 euros. Therefore, the final tax liability of MNECo1 is 2,500,000 euros.

The Pillar Two GloBE rules allocate CFC tax incurred by MNCo1 to MNECo2. This will increase its adjusted covered taxes, increase its Pillar Two GloBE ETR and reduce any top-up tax payable for MNECo2.

This is beneficial given the lower rate of corporate income tax in Country B. However, given the CFC income relates to foreign passive income the push-down limitation needs to be considered.

The tax allocated to MNECo2 is restricted to the lower of the actual amount of covered tax that relates to the passive income in the parent jurisdiction and the top-up tax percentage in the subsidiary jurisdiction multiplied by the subsidiary’s passive income taxed under the CFC/hybrid regime.

The actual amount of covered tax in MNECo1 is (5,000,000 * 20%)- 500,000 = 500,000 euros.

The top-up tax percentage in Country B is 5% (15%-10%).

Applying this to the 5,000,000 euros passive income taxed in MNECo1 results in tax of 250,000 euros.

As such although the actual amount of CFC tax in MNECo1 is 500,000 euros, only 250,000 euros can be allocated to MNECo2 for its adjusted covered tax calculation.

The remaining 250,000 euros remain with MNECo1.

The final Pillar Two GloBE ETR calculation for MNECo1 would be:

Income = 10,000,000 (as the Pillar Two GloBE Income is reduced by the CFC income)

Covered tax = 2,000,000 + remaining CFC tax of 250,000 = 2,250,000

ETR = 22.5%

The final Pillar Two GloBE ETR calculation for MNECo2 would be:

Income = 7,500,000

Covered tax = 750,000 + allocated CFC tax of 250,000 = 1,000,000 euros

ETR = 13.3%

If there was no CFC pushdown limitation, the MNECo1 Pillar Two GloBE ETR would be 20% and MNECo2’s Pillar Two GloBE ETR would be 10%.

This would have had the effect of reducing top-up tax in Country B with no Pillar Two impact in Country A as its ETR is above the 15% global minimum rate.

Domestic Differences

Whilst the CFC Pushdown limitation attempts to limit the CFC pushdown, in order to keep the rules as simple as they could be the OECD uses a bright line test with a list of payments that are subject to the CFC limitation.

However, in many jurisdictions, the domestic CFC provisions go much further than this. Generally passive or mobile income are types of income taxable under CFC rule but a more fact-based analysis may be applied domestically.

For instance, whether a CFC has substantial activities in a country and is not simply incorporated with a tax planning purpose.

Spain’s CFC provisions can apply when a foreign company does not have an adequate structure (eg HR or, material operations) unless it can be justified that there is a specific reason for the existence of the foreign company. If the purpose of existence of the company is not demonstrated and there is not material evidence of the existence of the company, all the income derived from it has to be included in the tax base of the Spanish parent company.

Japan’s CFC rules specifically applies a series of active business tests:

– main business test,

– substance test,

– management and control test,

– local business test or unrelated party test

The Commentary to the Model GloBE Rules specifically rules out any determination of whether there is an active business.

The US GILTI rules adopt an excess profits analysis with the calculation of a normal rate of return that then is subtracted from income earned by the CFC; the difference between these two is treated as CFC income.

There are therefore significant differences between the application of the CFC limitation in the GloBE rules and the application of CFC taxes domestically, with the latter having a much wider scope in certain jurisdictions.

This would further enhance cross-border jurisdictional blending, with the CFC tax paid on the income covered by the parent entity’s CFC rule allocated to the low tax jurisdiction. It would then be blended with low-taxed active income to increase the ETR for the low-tax jurisdiction, reducing the amount of top-up tax.

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |