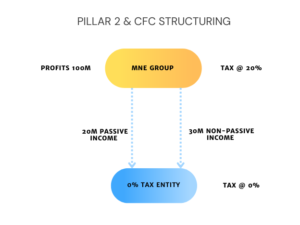

In this analysis we look at the key corporate tax incentives and assess their potential FDI impact taking into account the Pillar Two GloBE Rules.

Tax Holidays

General

Tax holidays remain popular, particularly amongst developing countries. The nature of the tax holiday can differ drastically. For example, it could be a blanket tax holiday for taxable income of a new company for a certain number of years, or only for certain forms of income/trading activities.

Tax holidays present a number of challenges for tax authorities, not least because they encourage profit shifting without robust anti-avoidance provisions.

Existing business income could be transferred to the tax holiday company, the tax holiday company could be used to route interest or royalties through, effectively obtaining a tax deduction in a high tax jurisdiction and receiving tax-free income in the tax holiday company or intra group transfer pricing policies could achieve similar results.

The risk from the jurisdiction’s perspective is that a tax holiday may not encourage long-term investment in the jurisdiction, particularly after the tax holiday period has expired.

Pillar Two Impact

From a Pillar Two perspective, broad-based tax holidays are generally not a desired approach. Indeed, in its report on

Tax Incentives and Pillar Two, the OECD states that ‘…The value of providing tax holidays to in-scope firms is likely to be strongly affected by the implementation of the GloBE Rules, which should prompt a re-assessment of the use of these types of incentives…’. They also note that they are poor incentives for promoting investment.

Tax holidays that apply to all of the income of an in-scope company can significantly reduce the GloBE ETR particularly where the company is viewed on a standalone basis. If the MNE group had other entities in the jurisdiction that were taxed above 15%, jurisdictional blending would raise the overall jurisdictional rate, but the extent to which it does so would depend on the relative profitability of the entities in the jurisdiction.

The fact that tax holidays have a questionable impact on local investment also suggests that the

substance-based income exclusion generated may not be significant.

This is important as the substance-based income exclusion is a design element of the GloBE rules that gives some favourable results for in-scope entities that have real economic substance in the form of tangible assets or payroll.

In particular, even if there is a low ETR, the substance-based income exclusion can directly reduce any top-up tax due.

Therefore, to the extent that MNEs invest substantially in local qualifying assets/payroll, this can reduce or eliminate top-up tax which would then impact on the efficiency of the tax incentive given. In other words, if there is no top-up tax, the benefit of the tax incentive wouldn’t be negated.

This is therefore an important factor when assessing which tax incentives to offer to in-scope MNE’s.

Investment Tax Credits

General

Investment tax credits are typically given as a pound for pound reduction in the corporate income tax liability, for example, for investments in local R&D or in sectors that the government wishes to develop.

They are attractive in terms of encouraging inward investment as unlike a general corporate income tax reduction, they benefit only new investment, thus avoiding windfall gains to other companies with existing investments.

Giving an upfront tax credit that reduces corporate income tax payable (or in some cases that could be refundable) also eases potential liquidity issues for the investor.

Providing upfront investment tax credits is also attractive as it can be used to directly target tangible inward investment. This has a number of benefits, not least the potential benefits of the substance-based income exclusion for Pillar Two GloBE purposes.

Pillar Two Impact

In general, for Pillar Two purposes, an investment tax credit would be treated as a reduction in covered taxes. This should also be the treatment reflected in the financial accounts (and if not GloBE income and adjusted covered taxes would need to be amended to correctly show the tax credit as a tax reduction).

In some cases, a tax credit can be a

qualifying refundable tax credit. Under Article 10 of the

OECD Model Rules, a qualifying refundable tax credit is a refundable tax credit paid as cash or available as cash equivalents within four years from the date when an entity satisfies the conditions for receiving the credit. A common example of this could be an R&D refundable tax credit.

In order to be refundable, any amount of the tax credit that has not been used to reduce covered taxes (eg corporate income tax) is either payable as cash or cash equivalent.

In this case, it is treated as GloBE income and doesn’t impact on covered taxes for Pillar Two purposes, thus having less of a pushdown effect on the GloBE ETR.

Whilst a refundable investment tax credit would be an attractive incentive for in-scope MNEs, care would need to be taken by any jurisdiction looking to either implement a qualifying refundable tax credit or amend existing tax credits to ensure they qualify.

Refundable tax credits, unless properly targeted, can result in significant revenue losses for an implementing jurisdiction. In particular, this requires a cash payment by the tax authority, and it may be that the investment would not actually generate any long-term revenue receipts sufficient to cover the payment made.

If properly targeted, an investment tax credit (even if not refundable) can be attractive both for MNEs and implementing jurisdictions.

They provide a high targeted incentive to invest in local assets and may generate long term investment capital investment. The level of the investment and relative profits/GloBE income as well as the statutory tax rate and other GloBE adjustments would dictate the extent of any top-up tax.

Accelerated Depreciation

General

Another popular option is for jurisdictions to offer preferential expensing for certain assets. This could take the form of an immediate tax deduction for certain assets or allow the cost of the asset to qualify for tax relief over a shorter period.

As for investment tax credits, this can be beneficial if it targets investment in new purchases of qualifying investments. It effectively provides a larger reduction in the ETR on new investment at a lower revenue cost.

These assets can potentially also qualify for the substance-based income exclusion, which would give the MNE and the jurisdiction, the most bang for their buck.

Pillar Two Impact

Unlike investment tax credits, accelerated depreciation is a temporary timing difference and is taken into account in the

deferred tax provision in the financial accounts. As adjusted covered taxes for the purposes of the GloBE rules are based on the current tax and deferred tax provision in the accounts (with certain adjustments), the deferred tax on the timing difference would be included in adjusted covered taxes.

By including the deferred tax asset, the GloBE ETR will be less affected as it takes account of the fact that taxes will be due at a later stage. If there was no deferred tax asset, in-scope MNEs could be subject to Top-up Taxes in the earlier years where they can depreciate the asset faster and not in later years when the timing difference reverts. The deferred tax asset therefore adjusts Covered Taxes so that these timing differences are ignored.

The Pillar Two rules do include a deferred tax recapture rule that claws back deferred tax liabilities where the timing difference did not reverse within 5 years. In this case, in year 6 the in-scope MNE would need to calculate the amount of Top-up Taxes due in year 1 if the deferred tax liability had not arisen and pay Top-up Tax accordingly.

The deferred tax recapture does not apply to various deferred tax liabilities, including:

- Accelerated depreciation on tangible assets (Note: it does not include timing differences relating to the amortization of intangibles or goodwill)

- Costs of a license or similar arrangement from the government for the use of immovable property or exploitation of natural resources that incurs significant investment in tangible assets;

- Research and development expenses;

- De-commissioning and remediation expenses;

- Movements arising from fair value accounting;

- Foreign currency exchange net gains; and

- Insurance reserves and insurance policy deferred acquisition costs;

As such tangible assets are not subject to the recapture rule. They may also qualify for the substance-based income exclusion.

Given the reduced impact on the GloBE ETR and the potential for the SBIE, accelerated depreciation can therefore be an attractive incentive.

Investment Allowances

General

Investment allowances generally provide an enhanced tax deduction for qualifying items of expenditure. This could be assets or revenue expenses.

For instance, qualifying R&D expenses could qualify for a 200% tax deduction. The financial accounts would reflect the 100% deduction in calculating financial accounting profits, with the additional 100% deduction for tax purposes being a permanent difference.

Similarly, an asset may qualify for 200% immediate tax relief. The financial accounts would include deductible depreciation based on the useful economic life of the asset. For tax purposes, the full asset cost would be immediately deductible.

This would result in both a temporary and permanent difference.

The timing difference results from the 100% asset cost being immediately deductible for tax purposes but deducted over a number of years for accounting purposes. This would therefore be a deferred tax liability (as above). The additional 100% tax deduction would be a permanent difference and is taken into account for Pillar Two purposes.

As for an investment tax credit, investment allowances are attractive as they can be focused on attracting new investment.

Unlike an investment tax credit, the value of an investment allowance to an MNE is partly dependent on the corporate income tax rate in the jurisdiction. A higher tax rate provides a higher tax saving. This arises as an investment allowance directly reduces the taxable base.

An investment allowance could also arise from providing an exemption for certain forms of income. This would also be a permanent difference.

Pillar Two Impact

As above, the timing benefit is included in the deferred tax provision in the financial accounts and flows through into adjusted covered taxes for Pillar Two purposes. As such, there would be limited impact on top-up tax.

Any element of an investment allowance that is a permanent difference will impact on adjusted covered taxes and have a more significant impact on the GloBE ETR than a timing difference.

However, there could be significant differences under Pillar Two from providing a tax exemption as opposed to an enhanced tax deduction.

Just for investment tax credits, an enhanced deduction is an expenditure-based tax incentive that is more targeted at the acquisition of qualifying assets or other expenditure. It therefore provides more opportunity for the benefit of the substance-based income exclusion to be available.

By contrast a partial exemption is an income-based tax incentive that is not directly linked to inputs but is referenced to outputs (ie it exempts income generated from an activity). As such, it is questionable whether this would encourage the acquisition of similar levels of local assets and payroll that can benefit from the substance-based income exclusion.

This is important as the substance-based income exclusion permits jurisdictions to offer tax incentives to promote qualifying expenditure with a reduced impact on the GloBE top-up tax.

This is a win-win for both the jurisdiction and the in-scope MNE.

Reduced Corporate Income Tax Rates

General

As highlighted above, one of the policy drivers for the Pillar Two GloBE rules is to end the ‘race-to-the-bottom’ with jurisdictions competing on corporate income tax rates to increase inward investment. See our

Global Corporate Income Tax Map for information on worldwide statutory corporate tax rates.

A reduced corporate income tax rate could be a broad-based reduction applying to all taxable income, or more targeted and apply to income of certain activities, certain revenue levels or certain activities. It could also be permanent or temporary.

Whilst reducing corporate income tax rates has the disadvantage in that it allows existing companies with established activities and investments to benefit from the rate reduction (unless it was targeted at newly established enterprises, but this then raises other issues in terms of anti-avoidance rules to avoid churning of existing income into the new enterprise), it does have advantages.

Most notably in terms of attracting inward investment, there is a clear benefit to MNEs (ignoring Pillar Two) for income to arise in a low-tax jurisdiction, and to book expenses in a high tax jurisdiction.

Of course, this is less relevant with Pillar Two.

Pillar Two Impact

A reduction in statutory corporate income tax rates that resulted in a

GloBE ETR below 15% may yield no benefit to the jurisdiction (unless there was a qualifying domestic top-up tax in place) and would see tax revenue being paid to a foreign jurisdiction. The incentive itself may provide no benefit to either the jurisdiction or the MNE.

The impact on the GloBE ETR would depend on the scope of the rate reduction and how it impacts on in-scope MNEs in the jurisdiction.

A broad-based corporate income tax reduction would have a significant impact on the GloBE ETR. The impact on actual top-up tax would depend on whether the corporate rate reduction encouraged significant expenditure that would qualify for the substance-based income exclusion, when compared to GloBE income.

Whilst there’s little doubt that a corporate tax rate reduction can incentivise investment, there is less evidence that it is directly linked to significant investments that would qualify for the substance-based income exclusion.

Tax incentives that encourage a high amount of substance in a jurisdiction relative to GloBE Income are attractive in a post-Pillar Two environment.

As such, tax incentives where the scale of tax relief is more tightly associated with the amount of economic substance, are less impacted by the Pillar Two GloBE rules.

It’s also worth noting that tax incentives targeted to specific types of income, such as IP or export income, effectively set a limit to the total impact for an MNE that is subject to the reduced rate.

As the Pillar Two ETR is calculated on a jurisdictional basis, the impact of such incentives on the GloBE ETR is therefore likely to be smaller if an MNE had multiple entities in a jurisdiction.

If all income in the jurisdiction was subject to the reduced rate, blending would not make any difference, at least as it applies to the tax rate.

Conclusion

Given the importance of the substance-based income exclusion in determining Pillar Two top-up tax, expenditure-based incentives that are tightly defined to encourage qualifying investments are one of the key tax incentives post Pillar Two.

Accelerated depreciation also has an added advantage given its lower impact on the GloBE ETR. After Pillar Two, tax incentives that have an effect on the composition of foreign direct investment as opposed to just the level of investment will be even more important.

Income-based incentives potentially have more of an impact on the GloBE ETR and therefore need to be carefully considered.

There is certainly no ‘one size fits all’ approach and dependent on the nature and scope of the incentive, as well as the general investment climate they can still be beneficial, particularly where jurisdictional blending can apply to uplift a low ETR of one entity in a jurisdiction.